Who Really Took the Iconic Napalm Girl Photo? A Look at The Stringer Documentary

Yvan Cohen

Mon Dec 08 2025

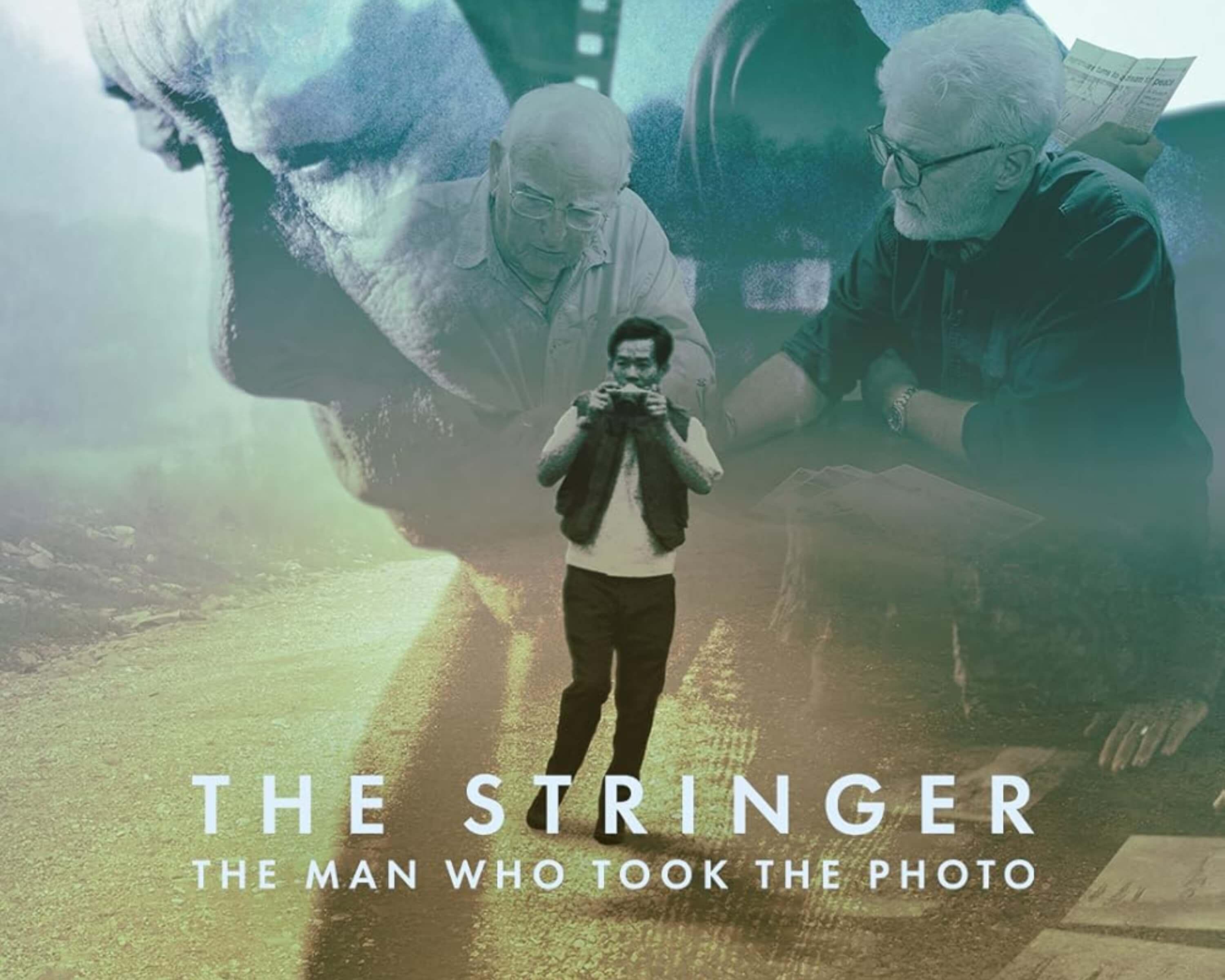

The Stringer a Netflix Documentary

The Stringer has all the ingredients of a hit documentary. It claims to reveal a historic injustice and expose a long-hidden truth, while shedding a spotlight on the prejudices of the Western media during the Vietnam War.

The film suggests that an image long considered one of the most potent reminders of the truth of war is, in fact, underpinned by a lie.

What The Stringer Is About: The Napalm Girl Photographer Controversy

As The Stringer tells it, the Napalm Girl (also known as the Terror of War), which has always been credited to Vietnamese photographer Nick Ut, a staffer for the Associated Press, was actually taken by an unknown and, till now, forgotten Vietnamese stringer (freelancer) by the name of Nguyễn Thanh Nghê.

The narrative is built around a perpetually earnest-looking Gary Knight, the grizzled British co-founder of the renowned VII photo agency and a leading figure in the world of photojournalism.

Cast in the role of globe-trotting sleuth, Knight takes it upon himself to investigate the claims of 81-year-old American whistleblower Carl Robinson, who says his boss in AP’s Saigon bureau, Horst Faas, ordered him to wrongly attribute the Napalm Girl picture to Nick Ut. Of the four people in the room at the time, all but Robinson are now dead.

For his part, Horst Faas, who died in 2012, has always maintained, including in comments made close to the time of his death, that nothing untoward occurred in the attribution of the Napalm Girl.

The controversy revolves around events that took place on June 8th, 1972, when the Vietnamese Air Force mistakenly dropped napalm bombs on the village of Trang Bang, some 40 kilometers from Saigon.

A clutch of foreign and local reporters on the road at the moment of the attack witnessed villagers fleeing the inferno. Among them was a terrified 9-year-old Kim Phuc, who is seen running naked, arms outstretched, her face contorted in agony, as scorched skin peels from her tiny body.

An ITN TV crew recorded the scene, as did a number of photojournalists including Nick Ut, the stringer Thanh Nghê, several other local photographers, and David Burnett, who was on assignment for Time and Life. Burnett, who declined to be interviewed for The Stringer, has always vocally maintained that Ut is the author of the picture.

In the ensuing half century, Nick Ut has regularly recounted in detail how he captured the Napalm Girl picture that day. The picture has earned Ut numerous accolades, including a World Press Award for Press Photo of the Year in 1972, and a Pulitzer Prize for Spot News Photography in 1973.

"Napalm Girl" by Nick Ut

"Napalm Girl" by Nick Ut

Horst Faas, AP, and the Napalm Girl Photo Credit Debate

The makers of The Stringer are at pains to present their documentary as a serious piece of investigative journalism, but one is never in doubt as to its conclusion.

“It’s not my job to tell you what to think,” said Gary Knight during a recent presentation at the Foreign Correspondents Club of Thailand (FCCT) in Bangkok, before going on to say he believed the documentary had proven “beyond all reasonable doubt that Nghê had taken the picture.”

And yet if there is one emotion The Stringer has spawned in abundance, it’s doubt.

The film has prompted acrimonious arguments between its proponents and those who believe it overlooks too many questions; taking at face value information that, fifty years after the fact, has been blurred and scrambled by the passage of time.

The two villains of the tale, Horst Faas and the Associated Press, occupy only a marginal space in the film.

Faas is largely portrayed through the commentary of Carl Robinson, who was clearly not fond of his boss.

And though we are shown an attempt to contact the Associated Press by phone, after which Knight describes his counterpart as ‘very, very open’, we are led to understand that the Associated Press had declined to take part in the documentary (apparently, they did so because of the filmmakers’ requirement that AP sign a Non-Disclosure Agreement, barring them from any commentary prior to the film’s release).

Nick Ut. Photo by Richard Vogel

Nick Ut. Photo by Richard Vogel

Further Allegations Challenging Nick Ut’s Authorship of Napalm Girl

In May this year, AP released its own investigation of the Napalm Girl controversy. The 97-page report provides a fascinating and highly detailed complement to The Stringer’s claims. Statements drawn from AP’s report were apparently hastily added to the Netflix version of the film released last month, probably at the request of the company’s lawyers.

Cited in AP’s report, a Vietnamese Secretary present in the Saigon bureau at the time, known as Miss Tu, describes Faas as “very generous”. She goes on to counter Nghê’s claim that he was paid just US$20 for the roll of film from which the Napalm Girl was selected, asserting that “if Horst Faas paid for that photo — it was very important — he would never pay $20. When the man says he was paid 20 bucks, that’s wrong. I don’t believe it.”

Referring to the alleged miscrediting of the Napalm Girl picture, she adds “no, we never talked about it. We never heard of that before. One hundred percent no one brought this up. Nothing was ever said. We were a friendly office, we only had a few Vietnamese people there, only four or five. We never heard anything about it, about that photo, until last year.”

The film portrays Faas’s attitude as part of a broader pattern of discrimination towards local journalists, characterizing both Nghê and Ut as victims of forces beyond their control.

Asked if Faas made a habit of miscrediting the work of local photographers, Carl Robinson could not remember a single other example of him changing attributions as he is claimed to have done with the Napalm Girl picture.

The film suggests that Faas’s actions might have been motivated by guilt, because he had recently sent Nick Ut’s brother on an assignment during which he was killed.

Even so, it seems odd that a senior editor, who was an experienced combat photographer and had mentored and helped local photographers, would have abandoned his ethics to make such a dishonest and unprofessional gesture.

At the time when the credit was allegedly changed, nobody could have known the impact the photo would have. Given this, and the controversial nature of the image itself, it’s hard to see what benefit Faas would be conferring on Ut, who is described by the surviving office secretary as a ‘very honest young man’.

Source: Associated Press

Source: Associated Press

AP’s Policies, and Robinson’s Claims Against Nick Ut

Horst was clearly a forceful character and something of a maverick. He was also renowned as an extremely courageous photographer, considered to have produced some of the finest images of the Vietnam war.

In choosing to distribute the Napalm Girl picture that day, Faas was breaking with AP norms, which forbade the depiction of nudity and children. Robinson himself was opposed to sending out the picture. In its report, AP refers to a memo Robinson wrote in 2022 in which he talks of ‘pedo war porn’ and calls Nick Ut a ‘false idol’.

If the argument is that Faas attributed the picture to Ut because he was a staffer and he wanted AP to enjoy the full credit, one could equally speculate that it would have been in Faas’s, and AP’s, interest to attribute the picture to a stringer, thereby distancing themselves from any direct criticism of its shocking content.

As impassioned as it is, and as credible as he sounds, Robinson’s testimony is clearly not neutral. Robinson was dismissed by AP in 1978 for unknown reasons, and in his autobiography recounts his “simmering anger, resentment and bitterness, especially towards AP.”

Index’s Forensic Analysis Supports The Stringer’s Claims

The Stringer’s strongest case for Nghê having taken Napalm Girl rests on the testimony of a French company, Index, hired to produce a forensic analysis of the events and movements in Trang Bang.

Using complex arithmetic, animated 3-D modelling (since described as “flawed” by AP), and satellite imagery, the filmmakers seek to prove beyond doubt that Nick Ut could not have taken the famous shot.

It's the kind of expert testimony designed to convince a jury (the viewers) and win the case. And the evidence is indeed compelling.

But what appears irrefutable when presented in neat units of geometry, velocity and geography, is less so when one considers that the bases for these calculations are drawn from assumptions that are neither completely reliable nor perfectly accurate.

In its report, AP points out that “any effort to reconstruct what happened on the road using available footage is going to be imperfect, with a wide margin for error.” Cuts in the footage used in the reconstruction leave unresolved time gaps. AP also notes that the filmmakers denied them access to Index’s full report.

We are left, therefore, with yet more questions and more doubt. Though The Stringer may trace a satisfying arc towards the inevitable ‘truth’ of Nghê having taken the Napalm Girl photo, the reality is that there can be no certitude.

The filmmakers are, of course, right to raise questions about Nick Ut’s authorship. Other factors, such as his claim to have been photographing with a Leica when forensic examinations of the film suggest it was taken using a Pentax, cast further doubt over his authorship.

For his part, Nghê says he was given a print of the Napalm Girl by Faas (which seems like an odd thing for Haas to do if he had credited it to someone else), but that the print was subsequently torn up and thrown away by his wife, who was offended by its content.

Did Nick Ut Really Take the Napalm Girl Photo?

None of the evidence presented by either the filmmakers or AP leads us to an irrefutable truth. Too many of the key witnesses are dead and the passage of time has made it too difficult to know with certainty what happened on June 8th, 1972, in Trang Bang.

So, what are we left with? A film that frames a legitimate question in a relatively entertaining format.

Try as it may; The Stringer reveals no burning truth. The only truth that remains untouched by this controversy is that of the Napalm Girl photograph itself; in its depiction of the terror and horror of war.

Written by Yvan Cohen | Yvan has been a photojournalist for over 30 years. He's a co-founder of LightRocket and continues to shoot photo and video projects around Southeast Asia.

To read more helpful articles on photography, check out our blog page.

Join our growing photographer community at LightRocket and get powerful archive management and website building tools for free!